Dissecting a Chicken Wing

Learn about the bones, muscles, ligaments, and tendons in your own arm, with a cheap, simple kitchen project.

Most of the “higher animals” have body plans very much like those of human beings — four limbs, a head on top with two eyes and two ears, a torso with a chest and a belly, and so on. And the more that an animal is like us on the outside, the more it will probably be like us on the inside, too. So if we look inside another mammal or even a bird, we can get a pretty good idea of what we ourselves are like on the inside.

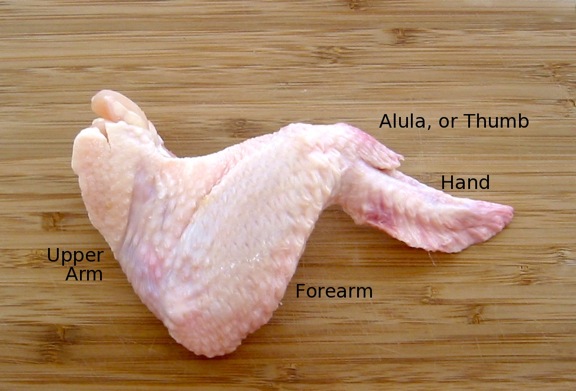

Chicken wings are cheaply available at most meat counters, and provide a nice analog to a human arm. Assuming that you can find whole wings (not “party wings” or wing sections) then you can discover that a chicken wing has three sections, roughly in the same way that the human arm has an upper arm, a forearm, and a hand. The wing tip even has an "alula", which looks somewhat like a bird's version of a thumb.

If you feel for the bones through the flesh, you may also discover that there is a single large bone in the upper arm

, just like the human humerus, and two long bones in the forearm

, like the human ulna and radius. There are also several smaller bones in the hand

. If the bone structure is similar to that of a human arm, what about the arrangement of muscles and tendons? Will there be two big muscles on the front and back of the upper arm

that bend and straighten the elbow

, like the biceps and triceps muscles in humans? Will there be a bundle of muscles in the forearm

that move the hand

? It is easy enough to remove the skin from a chicken wing, observe the muscles and tendons directly, and find out.

The tricky part is to remove the covering of skin without damaging anything underneath. The skin is loose in many places, so it peels up fairly easily. But it isn’t completely free, either. It is stuck down tight to the bone at the trailing edge of the ulna, it is stuck down pretty firmly around the hand, and in other places it is interwoven with the muscles in a tangled network of connective fabric (fascia).

In rough terms, you need to peel the skin off of the muscles and other fabric underneath, starting with the shoulder and working your way out towards the wing tip. Exactly how you do this is a matter of technique. I have done it with a scalpel and dissection scissors, but I think it works best with a dull flat blade, like a simple pair of kitchen shears or even a butter knife: Slip the blade sideways between the skin and the muscle (or meat) at the open shoulder joint, and gently work the blade back and forth, gradually loosening the skin and unsticking it from the muscles and fascia underneath. Continue working the flat of the blade gradually side to side, forcing it between the skin and the underlying tissue. You can then pull off the skin by hand. You may find it easier to cut and peel in strips, working your way in steps from the shoulder towards the wingtip.

I have also used a scalpel to cut and scrape the skin free from the material underneath, but in general I think that tearing works better than cutting. The connective fabric tends to tear most easily between skin and muscle, which is what you want, whereas a scalpel instantly cuts whatever it touches and too easily damages fabric that you don't want damaged. Chicken wings are quite cheap, so you may want to practice the dissection several times. (Incidentally, I've never tried thawed frozen wings, so I have no idea if they work as well as fresh wings.)

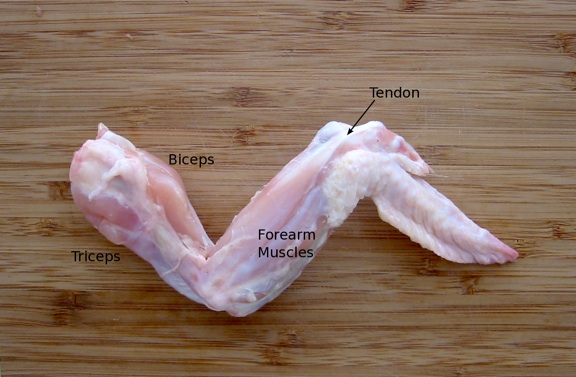

With a little care and practice, you should be able to remove most of the skin on the upper arm

and forearm

, and maybe some of it around the wrist

and on the hand

as well. Here is an example of a wing that has been (mostly) skinned:

The upper arm

does indeed have two large muscles, one on the inside of the elbow

, just like a human biceps, and one on the outside, like a human triceps. And each of these large muscles has a tendon running to the forearm

. When you pull on each muscle, you will find that it does the same job as the corresponding muscles in the human arm. If you pull on the biceps, it will fold the elbow, and if you pull on the triceps, it will straighten the elbow. Furthermore, the forearm

has a bundle of muscles with tendons running into the hand

that make the hand move, just as muscles in the human forearm work the human hand.

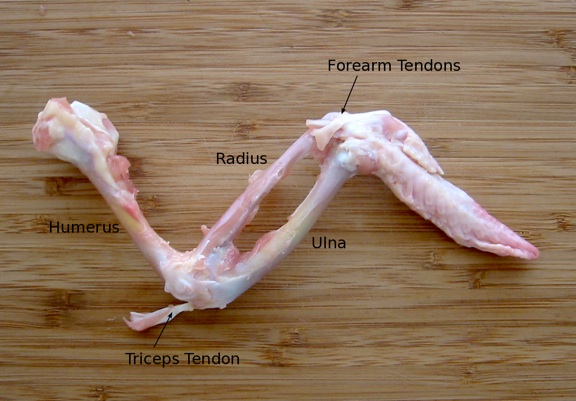

Once you are done examining the muscles of the arm, then you can trim them from the bones and reveal the three “arm bones” underneath. If you are careful about where you cut the tendons, you may be able to preserve the joint capsule surrounding the elbow joint

where the three arm bones come together, and observe how it remains sealed even as you move the joint.

How does your body hold your bones together so strongly at the joints, yet still allow them to slide against each other without grinding and without wear-and-tear? If you carefully break open the chicken's elbow

joint, you may be able to find out. You might be able to observe a small amount of oily fluid leak out just as you break the joint, and you should notice some slick cartilage covering the bones where they meet. The joint capsule helps to hold the bones together, but it also holds in some oil to help lubricate the joints, keeping the bones slippery where they meet and helping them slide smoothly against each other. The oil

is officially known as synovial fluid, and the slippery covering over the ends of the bones is articular cartilage. (Why is the joint so hard to break open? You might notice that portions of the joint capsule are extra fibrous and tough. Strong ligaments bind the joint together, and these ligaments are often interwoven into the fabric of the joint capsule. Unfortunately it is hard to get a good look at the ligaments by themselves, because the entire joint capsule is a cobweb of tough inter-grown tendons, ligaments, and fabric to seal in the oil. You may have damaged some of the ligaments or the capsule when you were removing the muscles. That's easy to do, because the muscles' tendons often grow into the tangled mess of fabric around the joint. Boiling helps to remove flesh and clean the bones, and may be a good way to discover the fine bones in the hand

, but it tends to dissolve the capsule and the ligaments, and tends to leave loose bones instead of an articulated skeleton.)

As long as you are playing with a chicken wing, here are a few more observations you may want to make, especially with the bones: If the butcher has sawed off the top end of the humerus

, you should be able to see spongy bone (also known as cancellous bone) within the bulb on the end. If he hasn't, you will see the rounded end intact and be able to observe the covering of articular cartilage. If you scrape the side of a bone, you may find a thin but tough fabric coating it — that’s the periosteum. If you break one of the bones in the middle (the thinner forearm

bones are easier), you will find that it is hollow with a red pulpy cranberry jelly

inside — that’s marrow, contained within the medullary canal.

So a chicken's wing and a human arm have a long in common. They are like variations on the same theme. What about a chicken's leg and a human leg? Are they the same, too? To find out, we'll have to dissect a chicken leg.